Lachine Massacre.

Burning the stores of the Mohawks in the fall of 1687 was to have consequences. And there was treachery involved. Kondiaronk, known to the French as "The Rat," was chief of the Huron (Wendat). Kondiaronk had been led to believe the French would not sue for peace with the Iroquois. Upon hearing of impending negotiations between the Five Nations and the Canadians, he, calculating his people would be safer if the Iroquois and French kept each other occupied, tricked the Iroquois into thinking they had been deceived by Governor Denonville. He ambushed the party on their way to meet the governor, then acted with mock astonishment when they described their peaceful mission. He claimed he was compelled to attack them and then he set them free to tell their people of the betrayal. A move that he later boasted "killed the peace."

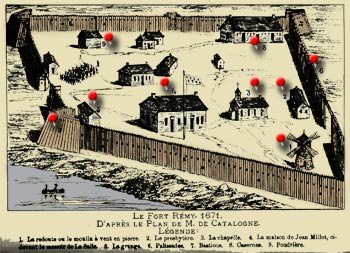

Lightly defended Lachine was in the sites of the vengeful Iroquois who felt it an easier target than nearby Montréal. The little settlement was protected by Fort-Rémy and two other stockades, Fort-Rolland and La Présentation, were within a few miles. The town itself was composed of whitewashed homes topped with high peaked roofs that kept the winter snow from piling up.

The Attack.

On 5 August 1689, under the cover of night, a large band of Iroquois armed with guns provided by the British and the Dutch, attacked the Lachine settlement which lay just outside of Montréal. The lightening and hail which preceded their assault perhaps caused the residents to nestle in; they were so surprised by the force of 1500 invading their small village that few had time to arm themselves in defense.

The brutality was complete. Fires were set to drive the settlers out of the safety of their homes. Horrified witnesses described children whose heads were smashed on doorposts and women cut down with tomahawks. By some measure they were the fortunate ones as numerous others were taken prisoner to be killed by a long drawn out torture of flaying or being burnt alive. The episode marked the beginning of a series of violent assaults by both parties.

Survivors scrambled to keep ahead of their attackers to reach the soldiers just a couple miles away. Other settlers in the area had been alerted by sound of cannon fire from one of the forts and armed themselves to rally to the aid of their neighbors but since the commanders were in Montréal that fateful night, there were no sorties sent from the forts to launch a counter attack. Between 60 to 90 settlers were slaughtered or lost between the initial assault and the subsequent deaths that followed.

Hearing the marauders had stolen large quantities of brandy and then settled in to celebrate the victory, commander Daniel d'Auger de Subercase rallied 200 soldiers from the forts and another 100 settlers to march against the now drunk and distracted Iroquois. But his forces were recalled to the fort where they were confronted with the corpses of several of the victims. The local commander, Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, had authority to respond, but did not until the following day, believing he was to hold a defensive position. Too late, by then the Iroquois had moved on. Canadians were enraged to find British supplied weapons among the guns abandoned by the attackers.

Aftermath.

Denonville sent out soldiers who met a war band of Iroquois at Lac des Deux-Montagnes. Eighteen Iroquois were killed, and three were captured. In reprisal for the deaths of the Lachine captives, the prisoners were burned alive in Montréal at the Palace Royale. Denonville's service in New France was at an end. His replacement was Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac. Denonville and his family departed for France in November where King Louis XIV promoted him to major-general.

Frontenac located the sachems who had been captured and sent by Denonville to serve as galley slaves. Of the 50, the 13 who survived returned with him in October of 1689 to be used as hostages. The gesture did little to belay the hostility.

- https://static.torontopubliclibrary.ca/da/pdfs/37131055411094d.pdf, Histoire du Canada... d'après un manuscrit à la Bibliothèque du roi à Paris, by Belmont, François Vachon de, 1645-1732, Year: 1840

- Wow wiki/Lachine_massacre#cite_ref-32

- https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WMK9KD_Fort_Rolland_Montral_Qubec_Canada

- https://ville.montreal.qc.ca/portal/page?_pageid=8197,90717686&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL

- Dictionary of Canadian Biography, BRISAY DE DENONVILLE, JACQUES-RENÉ DE, Marquis de DENONVILLE