Capture and Imprisonment 1689 – 1692.

Capture.

August 6th, the day after the massacre, the 27 year old Clément Lerigé LaPlante was part of a detachment of 50 soldiers and 30 Indian allies out of Fort-Remy. This was all Denonville felt he could spare to remove from the defense of the city of Montréal. It was under the command of Sieur de la Rabeyre out of Fort-Rolland which was on the shore of the Saint-Laurent river, a little more than a mile west of Lachine. The other officers included his second, Charles Le Moyne de Longueuil (II) , Saint-Pierre, Denis, Villedonne and our LaPlante. The hundreds of now-sober Iroquois met them with ferocity. In the mêlée that followed Le Moyne, his arm broken (or thigh depending on the source) and otherwise wounded by allies, was helped to Fort-Rémy by four of the same group. Only twelve allied Indians and one soldier escaped. The rest of the men "were either taken or cut in pieces".

Several officers were taken prisoner; La Rabeyre, La Plante and Villedonne were brought to the Iroquois village. One of two outcomes awaited the captives. They would be tortured and sacrificed, or they would be tortured and allowed to live. Lieutenant Rabeyre was burned alive and eaten in a cannibalistic ritual at Sault Saint-Louis. Etienne de Villedonne escaped or was liberated at some point; he does reappear in later records. Our ancestor, Clément Lériger Laplante was kept alive "after many tortures" and sent to the Onondaga homeland south of Lake Ontario.

Imprisonment.

Having survived the initial ordeal, which may have included burning, being cut up and beaten - our ancestor describes having to walk upon hot coals as part of his trials - the prisoner would be turned over to a matriarch who would determine the actual role of the individual within the village. Often captives would serve to replace members of the community lost to battle or disease. Though some would integrate, most would be relegated to "burdeners" taking on work to support the needs of the community. Death awaited those who resisted. At best, they could hope to be part of a prisoner exchange as both sides sought to free their own people from the hands of their enemy.

Life Among the Onondaga.

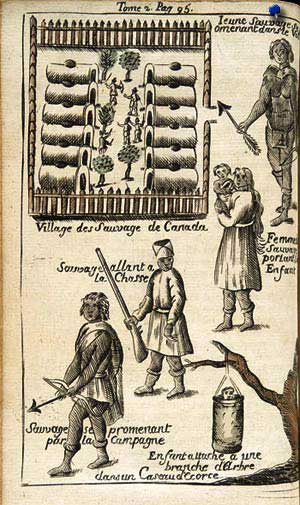

The Iroquois or Haudenosaunee, of whom the Onondaga people were a part, lived in large longhouses. The structures were home to several families. Poles were used to frame the long, narrow building. The curved roof of birch bark or animal hide was affixed using leather strips. A flap covered the doorway, and holes were cut in the ceiling to release smoke from the cooking fires positioned along a corridor through the middle of the building. A palisade of logs surrounded the homes as added protection for the settlement.

Women were the farmers, seeing to the corn and beans. They took care of the family and oversaw the property. They also had the power to choose the men who would represent the tribe in the councils. The men conducted any trade negotiations, fished, hunted the deer and elk, and determined when and if the community would take part in war.

Lériger lived among them for the next three years in the area of Lac Saint-François on the Saint-Laurent between Lake Ontario and Montréal.

- https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/026017/f1/nlc004102-v6.jpg

- New Voyages to North-America, Volume 1 By Louis Armand de Lom d'Arce baron de Lahontan, Reuben Gold Thwaites, Victor Hugo Paltsits

- Le vieux Lachine et le massacre du 5 août 1689, Désiré Girouard, Editeur, Cie d'imprimerie et de lithographie Gebhardt-Berthiaume, Montréal, 1889

- Our French Canadian Ancestors, Thomas J. LaForest, (III-rev) p127-134

- https://static.torontopubliclibrary.ca/da/pdfs/37131055411094d.pdf, Histoire du Canada... d'après un manuscrit à la Bibliothèque du roi à Paris, by Belmont, François Vachon de, 1645-1732, Year: 1840

- Academia: .edu; Events As Seen From the North, The Iroquois and Colonial Slavery, William A. Fox

- Onondaga Indian Fact Sheet