René Plies His Trade.

Stone Mason.

When men cleared the forests for fields to farm they used the felled trees to build their homes. But as the settlements grew into towns masons were called upon to build sturdier homes and hardworking mills. And the danger of fire in the cities prompted new rules in later years requiring houses to be made of stone rather than wood.

Colossal structures like cathedrals and palaces were built of the most durable material available, stone, to stand for centuries. A stone mason was at the top as far as tradesmen were concerned for it was only he who understood the mysteries that held the massive blocks together in a manner that prevented the whole structure from collapsing in a heap.

The job had many hazards. Among the risks they faced were blindness from sharp chips flying while honing the stone, or falls from the heights they had to scale to lay the heavy blocks.

The quarries around Cap Rouge and the Québec promontory provided a greyish limestone that was used on many of the buildings in the city. Quarrymen cut large blocks from the site, likely using a wedge device called a plug and feather. They then loaded the blocks on a barge to ship along the river to the mason at the building site. Pierre Petel was among those who navigated the river with such a cargo.

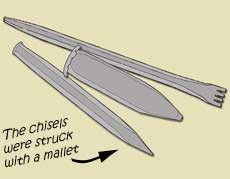

The hammer and chisel the mason used to shape the blocks have been used for ages. René chose a metal chisel with a wider point when working with a soft limestone, while a harder granite yielded to a sharper point. A tooth chisel evened out the marks from a rough cut, then the stone surface was finished with a smoothing tool.

As a tailleur de pierre (stone cutter) René knew how to shape the material to add architectural elements such as arches over entrances, stairs or lode-bearing vaults in ceilings. His knowledge included a grasp of the necessary geometry needed to safely construct the structure.

- Dan Petelle, Stonemason, Kingsport, Tennessee

- https://oldstonehouses.com/tag/17th-century-stone-masonry/

- The Art of Making in Antiquity, stoneworking-tools

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tailleur_de_pierre