Life on the Farm.

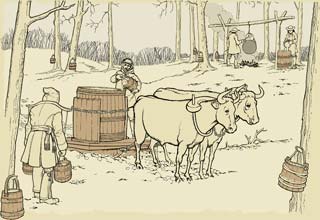

Families were self-sufficient units and firmly tied to the land. Even when grain crops failed, as they had in recent years, farmers could rely on their vegetable gardens, cows and chickens to sustain their large families. Their long held traditions influenced daily life. When the oiseau de sucre arrived in the spring, it was time to tap the nearby maple trees. The entire family would be engaged in this enterprise. Once the tree was tapped, the sap ran down boards into wooden buckets which were emptied into larger kegs. Forty gallons of sap was required to make about a gallon of syrup. During the season, hundreds of gallons of sap were boiled to make enough syrup and sugar needed for a year. It was an intensive operation, but one met with a festive atmosphere. The syrup was used extensively in cooking. Boiling the syrup down further produced maple sugar. The technique was adapted from that of Native Americans who called the maple sugar sinzibukwud. The French molded the sugar into one or two pound blocks called pains de sucre.

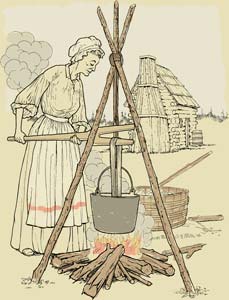

In the spring, Charlotte arranged a trip for the family to the nearby woods to gather blueberries in their tin pails. Some were served with dinner, some went into delicious pies, and the rest were canned to eat throughout the year. The meals she prepared were wholesome. The family would awaken at about 5:00 am to the aroma of pancakes and salt pork or the occasional fried egg being prepared for the breakfast they would eat after their morning chores. The next meal could be left to simmer in an iron pot over flame as Charlotte helped with the crops or did other chores like tending the vegetable garden. The men headed to the fields, but returned home for the noon lunch of hearty pea soup. A saucer filled with maple syrup was placed on the table to dunk chunks of fresh bread.

The lunch was washed down with milk or water. Meats were served infrequently, and in keeping with their Catholic faith, never on Friday. A boudin was a special treat for the family. On the farm everything was used. Women rendered beef fat to make soap.

It was up to her to provide simple clothes for the family from the cloth she wove and scarves she knit. The women sewed household items like quilts or hooked rugs as needed. The coarse fabric they made from wool was called droquet. It was durable, making it suitable for the loose fitting pants the farmers wore. Adding suspenders, or a wide belt, moccasin-type boots and a flannel shirt completed the ensemble. During the long cold days the men would don a tuque or woolen cap (red was preferred around Montréal region) and an overcoat made of wool or animal skins. The coat was held securely by the colorful finger-woven ceinture fléchée, a colorful sash popular with fur trappers. The gingham bodice Charlotte wore in the summer was sewn from fabric she purchased. It was worn over a long flannel skirt, with an apron. A bonnet covered her head, topped off with a straw hat to shield her from the sun when she helped in the fields.

Running a farm was not limited to plowing, sowing the seeds and harvesting. Joseph and his sons likely built the furnishings used in their home, the loom his wife wove their clothes on, as well as a cart, and a sledge for winter travel. Though they relied on others for very little, their hospitality was legendary. Sundays, after mass, neighbors stopped by their home to share news and break bread. Travelers could count on a warm meal and place to rest their head before continuing on their journey.

- Masterclips eac022.tif, colored and cropped

- The French-Canadian Heritage in New England, The Roots of Franco–American Culture, pages 15, 26-27, 31-32 by Gerard J. Brault

- Maria Chapdeleine, by Louis Hémon, translated by W. H. Blake, Macmillan Co.: New York, 1921, p 32

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maple_sugar (July 8, 2009)

- Masterclips eac011a.tif, colored and cropped